Lea Lerma

L’Envers de l’Endroit

PART II

*10-minute study

Synopsis: Part II/II of Sunend's survey of Lea Lerma's L’Envers de l’Endroit explores the work through the discourses of Romanticism, cosmic unity, and modern-day disillusionment. Using ideas from art history, psychoanalysis, and visual theory, it looks at how Lerma creates a photographic style that moves between personal trauma, connection to nature, and spiritual depth. The images studied, ranging from muted mountain landscapes to eerie interior scenes, show a changing play of light, time, vulnerability, and inner change. The essay further highlights Lerma’s use of diagonal lines, broken narratives, and mystical tones, and presents her work as a modern expression of Romantic and spiritual traditions, shaped by today’s visual language.

Key references and methodology: This study uses a comparative visual analysis that combines historical context with symbolic interpretation. Drawing from interdisciplinary visual theory, including the work of Roland Barthes, Susan Sontag, and John Berger, it examines how Lerma composes her photographs and how viewers might respond to them emotionally and intellectually. Art historical references such as Goya, Caspar David Friedrich, and Rembrandt are used to situate Lerma’s formal strategies within a broader visual tradition. Hermeneutic and ethnographic approaches help explore her treatment of time, collective memory, and personal subjectivity, while an iconographic reading of recurring elements, like spirals, diagonals, and the shifting balance of light and shadow, uncovers their psychological weight. Finally, the study analyses how Lerma builds narrative through visual sequencing and non-linear storytelling. The main sources include her photographic series from 2020 to 2022, alongside historical artworks, philosophical texts, and critical essays, allowing for a pluralistic yet grounded interpretation of her work.

Romanticism, Cosmic Unity and Disillusionment

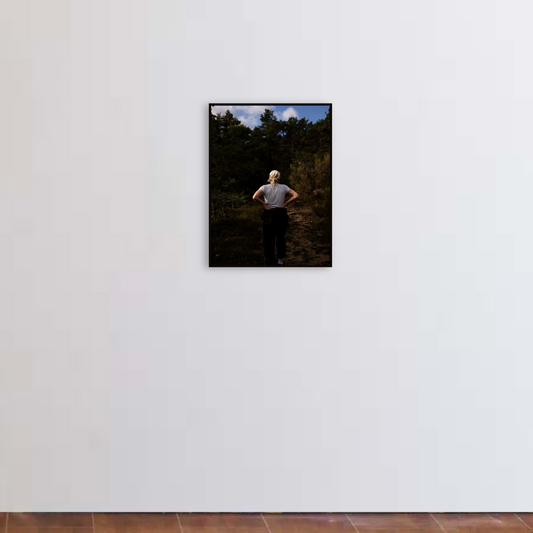

Across her Lerma's work, we find that her central visual interest lies in the relationship between the body and its environment. Philosopher Friedrich Schleiermacher redefined religion as an instinctual, interior experience (Butin, 2014).1 Lerma fulfils this yearning by uniting contrasting natural elements: light and dark, human and animal, earth and sky. In a heroic landscape scene reminiscent of Casper David Friedrich's best-known paintings, the mountain-scape merges with the infinite cloudless sky (Benesch, 1957), as the figure looks out at it.

Lisa dans la mer du nuages

Grenoble, 2020

Inkjet print

30 x 26 cm

Edition 1/5

Signed, numbered, and dated

£300

However, unlike Friedrich's figures, Lerma's figure appears unsteady, the spatial configuration vertiginous, suggesting a hidden dimension of the liminal communitas's "adventurous quest into an essentially fantastic world" (Flores, 1996).3 It is clear that her aesthetic mirrors the "abstract orientation of [her own] unconscious mind" (ibid.),4 and the quest is into the depths of the psyche projected outwards into the external world.

Pou, en pleine tempête

Sète, 2020

Inkjet print

30 x 26 cm

Edition 1/5

Signed, numbered, and dated

£300

In a dramatic scene, the unsteady stance of the figure depicts one of Lerma's friends almost merging with the force of the approaching storm. Despite the instability, a certain comfort is implied, as the figure considers the storm's power and danger, willingly delving into it (Coman, 2008). The lone figure amidst the storm evokes medieval and ancient imagery of sacrificial rituals, alluding to the suicidal urge to transcend towards the horizon (PGM IV, 960-74).6 The figure's white suit, matching the storm's fizzy, ephemeral froth, suggests a unity with the chaos.

It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is the invisible to the eye.

- Antoine de St. Exupéry, 19437

Hitchcockian Spiral

Lerma’s work has a strong affinity for the spiral motif, which Neil P. Hurley identifies in Hitchcock’s work as a spiral-like composition conveying vertigo, a state of whirling disorientation often accompanied by a sense of falling (Hurley, 1993).8 This technique evokes horror through helplessness, dizziness, and loss of control, with characters' lives precariously balanced. While both Lerma draws from Hitchcock’s use the spiral motif, their approaches diverge significantly, especially in how they evoke circularity.

The spiral motif in the opening sequence of Vertigo (1958) by Alfred Hitchcock. Source: imdb.com

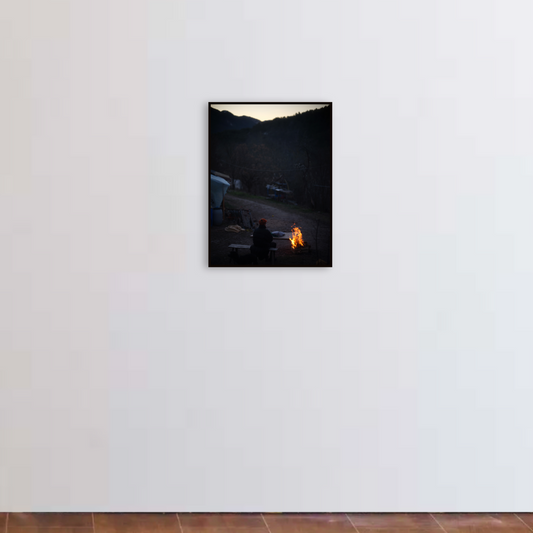

In Hitchcock's films, the spiral is aggressive and often crude, achieved through artificial manipulation of the camera or set design. In contrast, Lerma’s spiral is inherent within the structure of the image itself, and not externally imposed, imbuing the figures with a sense of already being inside of it. Her method conveys a more abstract, all-encompassing psychological experience, reflecting the subjects’ and the artist’s state of mind. This spiral can be seen in Lerma's works, such as the two figures with a goat at the cliff edge, the figure wading into the rising sea, the image of figures hiking and the one below with the figure next to the fire.

Agathe, attendant le soleil

Drôme, 2020

Inkjet print

30 x 26 cm

Edition 1/5

Signed, numbered, and dated

£300

Implied audience

Lerma's ethnographic process can be contextualised alongside Nan Goldin’s. Both capture "moments of isolation, self-revelation, and adoration" (Sussman, 1996)9 through intimate relationships. While Goldin’s work resembles photojournalistic snapshots, Lerma’s images are meticulously composed, creating a unique metaphysical visual language. Lerma adopts her ‘unprivileged view’ more subtly, allowing the viewer to engage with the subject and the scene without the artist’s presence intruding.

Pou, Lisa, Angèle, Laurent, Numa, Bianca, repos avant l'organisation d'une soirée

Lyon, 2020

Inkjet print

30 x 26 cm

Edition 1/5

Signed, numbered, and dated

£300

Unlike Goldin, Lerma’s subjects acknowledge her presence only partially, creating a relational space filled by the viewer’s psychological impulses. Art historian Alois Riegl, expanding on Hegel's appreciation for Dutch painting, notes that this viewer involvement reflects the artist's civic consciousness (Hertel, 1996).10

Suzanne and Philippe on the Train, Long Island, 1985 by Nan Goldin, Public domain, Artnet.

Light, Shadow, Colour and Divinity

Fairytales traditionally present a dichotomy between light and dark, with protagonists bathed in bright, divine light in a crystallised perfection as they journey toward a higher existence (Lüthi, 1987). In contrast, Lerma's pictures though aesthetically redolent of fairytale scenes are often muted, suggesting a sense of disillusionment. Her work dispels the utopian happily ever after trope, exploring a more nuanced relation to transcendence.

Lisa attendant le soleil

Drôme, 2020

Inkjet print

30 x 26 cm

Edition 1/5

Signed, numbered, and dated

£300

Junko Theresa Mikuriya links radiant light to the divine (Mikuriya, 2017),12 and while ancient Coptic-Egyptian and Greek magical texts (3rd-4th centuries CE) focus solely on light as "propellers of the rising of [the] soul" (ibid.),13 Lerma often emphasises shadows, reflecting the rhythm between light and dark, but somehow manages a similar effect, which is perhaps more haunting.

There’s a divinity that shares our ends, / Rough-hew them how we will.

- Hamlet, 5.2. 10-11

The effects of light in Lerma's work are shaped by her nuanced use of colour, but she does not prioritise formal elements of light, texture, structure, and colour over subject matter. Like Agnes Varda, Lerma focuses on the "conjunction of [these] elements and the relationships between them [that] are carefully chosen [...] to produce meaning from the interplay between them" (Smith, 1998).14 Her colour palette evokes Rembrandt’s "symphony of colours" and "counterpoint[s]" of cool, warm, and fiery tones (Benesch, 1957), using light that "ebbs and flows in softly throbbing waves" (Scott & Hillyard, 2019).16

Supper at Emmaus, c. 1628, Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, Public domain Wikipedia.

Rembrandt’s Supper at Emmaus (1629) exemplifies light’s transformative power, its ability to "spiritualise matter" and achieve "transubstantiation" (Benesch, 1957), a quality echoed in Lerma’s work through tonal gradations. Her tender, mellow atmosphere often features rich highlights against smooth, diffuse colour, evoking Rembrandt’s calm yet bold receptivity to the metaphysical. Unlike the theatrical Caravaggio or the repressed domesticity of Vermeer—both of whom Lerma mentions—her work embraces the transcendence within the ordinary. The subtle, evanescent light in many of her pictures, along with the occasional blinding white light, imbues her figures with a visionary, almost miraculous presence, making them feel like apparitions. Awe and suspense fill the air.

I call upon you, the living god, / fiery, invisible begetter of light…enter into this fire, fill it with a divine sprit, and show me your might. Let there be opened for me the house of the all-powerful god ALBALAL, who in this light. / Let there be light, breadth, depth, length, heigh, brightness, and let him who is inside shine through, the lord BOUĒL PHTHA PHTHA PHTHAĒL PHTHA ABAI BAINHŌŌŌCH, now, now; immediately; immediately; quickly, quickly.

- (PGM IV, 960-74)17

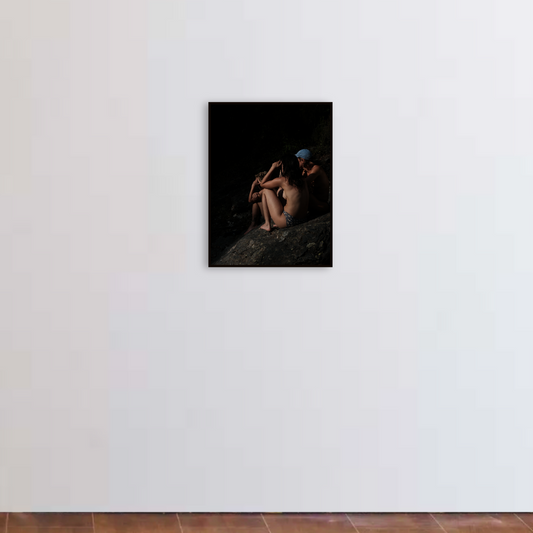

Progression of time through light and space

In many of Lerma’s pictures progression of time is explained by the use of light and space, which can be discombobulating. Similar to Goya’s The Third of May 1808, meaning unfolds in time through light and space, moving from the undifferentiated blurred background of ‘before’ to the stark, light-revealed climax of the execution— ‘now’—and finally to the blood-encrusted fallen figures at the boundary of the pictorial world, representing ‘afterwards.’ This progression is described by the intensification of light and colour saturation, and further by the shift from the blurred past to the sharpness of the present through the material texture (Nochlin, 1985).18

The Third of May 1808, 1814, Francisco Goya, Public domain, Wikipedia.

For instance, in the picture below, which has already been discussed earlier we see a clear example of the progress of both the light and the material texture of the elements culminating towards the viewer.

Pou, Lisa, et Angèle sur leur rocher

Cévennes, 2020

Inkjet print

30 x 26 cm

Edition 1/5

Signed, numbered, and dated

£300

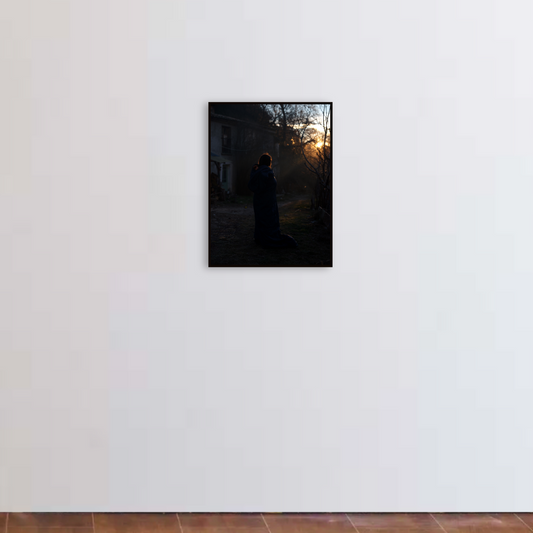

This progression of time from dark to light, or from undifferentiated blur to material crispness, can also reverse and clash with itself in a paradoxical progression of time. In some pictures, like the one below, meaning unfolds in opposite directions within the picture. The material texture of the space progresses from the blurry ‘before’ to the crisp clarity of the ‘now’ and ‘afterwards’ towards the viewer, while the light moves in the opposite direction, from the darkness of the past, where the viewer is positioned, to the intensified light and colour saturation of the present at the end of the opposite direction. This intersecting dual progression creates an unexpected visual effect, disorienting the viewer's sense of position, and holding the scene in suspension.

Roman faisant face à la fenêtre du sleeping

Lyon, 2022

Inkjet print

30 x 26 cm

Edition 1/5

Signed, numbered, and dated

£300

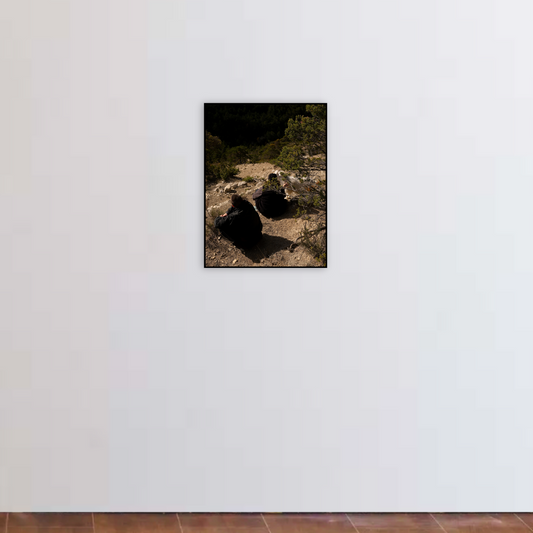

Diagonal Axes, Destabilisation, and Precarity: Lerma's compositions are meticulously structured with diagonal axes that either hold figures in place like someone caught in a spiderweb or, more often, tip them over, as if falling in a certain direction. Figures and landscape elements are frequently positioned on these axes, creating the impression that they are rolling out of the frame, destabilising the composition much like a spiral. A stark example is shown in the work below, where two figures squat near the cliff edge of a mountain, next to an ominous abyss into which they could fall. The diagonal axes starting from the right guide the direction of the figures and, the stones and other elements downward to the left, emphasising their precariousness both physically and psychically.

Pou et Mathilde, ascension en compagnie des chèvres

Drôme, 2020

Inkjet print

30 x 26 cm

Edition 1/5

Signed, numbered, and dated

£300

Discontinuities, asymmetries and open frames

While Lerma's work inadvertently embraces esoteric themes, the compositional approach avoids excessive aestheticism or constriction. Her work exhibits an analytical distance, devoid of sentimentality or nostalgia. As John Slyce (2000) metaphorically states, "The frame sets limits while at the same time,offering a tangible means of escape."19 Lerma strategically deviates from overly symmetrical,uniform, and spatially continuous compositions to loosen and relax them. This is achieved through various techniques:

Cropped sections: Elements within the scene are deliberately excluded from the final composition.

Lines leading out of the frame: Visual elements like pathways or a character's gaze draw the viewer's attention beyond the defined boundaries of the picture.

Figures interacting with elements outside the frame: The figures depicted engage with objects or individuals positioned beyond the frame's edge.

Awkward props: The inclusion of unexpected or incongruous objects within the scene disrupts its harmony.

Sol, chasse aux champignons

Drôme, 2020

Inkjet print

30 x 26 cm

Edition 1/5

Signed, numbered, and dated

£300

While diagonal axes in Lerma's work often induce feelings of instability, the techniques introduce fissures into any form of unity. In the above picture, intersecting axes of the various elements, focus attention, along with progressing light and material clarity, on the figure’s upper back, emphasising their physical strength holding them in almost a convex suspended in the mid-point. However, the unity is fractured by the figure’s angled arms that point askance, with the left towards the viewer and the right out of the frame. Additional complications include uneven, incomplete tree formations on either side, and an unexplained division of light, making the scene resemble a digitally rendered collage rather than a natural setting.

We have lost the art of describing the only reality whose structure lends itself to poetic representation: impulses, aims, oscillations.

- Mandelstam, Entretiens sur Dante

Polysemic potential of the photographic sequence

Lerma's work subverts traditional narrative arcs, focusing on "discourse units" (Van Dijk, 1985),20 where meaning emerges through the interplay of individual pictures. This mirrors the non-linear nature of human experience and aligns with the ethos of her communitas. Susan Sontag (2008) would describe Lerma's approach as "unsystematic, indeed anti-systematic.”21 This recalls Barthes' concept of the "punctum" (Barthes, 1980),22 where a photograph disrupts the viewer with unexpected details or emotional resonance. John Berger argues that this disruption stems from photography's inherent discontinuity, as each image isolates a moment, creating an "abyss between the moment[s] recorded" (Berger Bohr,1982).23

Lerma's visual storytelling is generative, juxtaposing disconnected moments to create an unordered constellation where echoes, contrasts and recurrences act as a form of "implicit intertextuality" (Ricœur, 1984).24 These connections, reminiscent of memory fragments triggering one another, compel us to participate in constructing meaning. While a particular sequence ultimately reduces ambiguity, each picture in the sequence is a turning point, a hinge. But Lerma's irregular sequential arrangements in different contexts exerts the independence and freedom of each picture from the weight of any sequentially narrated dogma.

Lea Lerma trying out different sequential orders for a recent project.

The potential of the single image

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1975) describes each individual moment, or picture, as "universal" and "particular."25 Each picture contains within it its particular self and the universal. Building on Eco's concept of "open text" (Eco, 1989), Lerma's picture resists a fixed dialogue, offering a multitude of potential narratives based on the viewer's background knowledge, cultural context, and the specific sequence in which the image is presented. This resonates with Barthes' (1977) notion of the "hermeneutic code,"27 where the elements within each picture give rise to an abstract general dialectic with the viewer. As Berger argues, the emerging language from an individual picture is and will always only be a half-language, as it "continually arouses an expectation of further meaning" (Berger & Bohr, 1982).28

Lea Lerma's pictures evoke mythical fairytale concepts, such as the desire for absolution. While classic fairytales portray external battles, Lerma's protagonists face internal conflicts. They coexist with ever-present dangers under reticent light amidst dominating shadows or conflicted by the obligation of a gift in the form of toxic wild fruit. Unlike those narratives, Lerma's works lack definitive closure. Resurrection is absent, replaced by a continuous flow of uncertain existence. However, instead of nihilism, we find the figures' subdued acceptance of the unknown, imbued with a melancholic serenity. This emotional state recalls Kirsten Dunst's character in "Melancholia," where Slavoj Zizek argues that the character's embrace of the imminent apocalypse as, in fact, a form of optimism (Fiennes, 2006). The prevailing mood is one of ambivalent optimism, reflecting a day-to-day existence devoid of grand, overarching drivers.

Part II Notes

1 Butin, Hubertus. Gerhard Richter’s Editions and The Discourses of Images. In Gerhard Richter Editions 1965–2013, edited by Hubertus Butin, Stefan Gronert, and Thomas Olbricht. Hanje Cantz, 2014.

2Flores, Nona C. Animals in the Middle Ages: The Book of Essays. 1996.

3 Ibid.[2]

4LiDonnici, Lynn R. “Compositional Patterns in PGM IV (= P.Bibl.Nat.Suppl. Gr. No. 574).” The Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists, vol. 40, no. 1/4, 2003, pp. 141–78.

5 Exupéry, Antoine de Saint. The Little Prince, translated by Katherine Woods. 1943.

6 Hurley, Neil P. Soul in Suspense: Hitchcock’s Fright and Delight. Scarecrow Press, 1993.

7 Sussman, Elisabeth. Nan Goldin: I’ll be Your Mirror. Whitney Museum of American Art, 1996.

8 Hertel, Christiane. Vermeer: Reception and Interpretation. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

9 Lüthi, Max. The Fairytale as Art Form and Portrait of Man. Indiana University Press, 1987.

10 Mikuriya, Junko Theresa. A History of Light: The Idea of Photography. Bloomsbury, 2017.

11 Ibid.[10]

12 Smith, Allison. Agnes Varda. Manchester University Press, 1998.

13 Scott, Jennifer, and Helen Hillyard. Rembrandt’s Light. London: Philip Wilson, 2019.

14 Ibid.[4]

15 Nochlin, Linda. Realism. Penguin Books, 1985.

16 Slyce, John. On Time, Performative Realism: The Photographs of Sarah Jones. Museum Folkwang, 2000.

17 Sontag, Susan. On Photography. Penguin Modern Classics, 2008.

18 Barthes, Roland. Critical Essays, edited by Richard Howard. Northwestern University Press, 1972.

19 Berger, John, and Jean Bohr. Another Way of Telling: A Possible Theory of Photography. Bloomsbury, 1982.

20 Ricœur, Paul. Time and Narrative, translated by Kathleen McLaughlin and David Pellauer. University of Chicago Press, 1984.

21 Hegel, Georg W. F. Philosophy of Right. London: Oxford University Press, 1975.

22 Ibid.[18]

23 Ibid.[19]

Full Bibliography

Barthes, Roland. Critical Essays, edited by Richard Howard. Northwestern University Press, 1972.

Bastide, Bernard. “‘Mythologies, me vous faites rêver’ ou mythes caches, mythes dévoilés dans l’œuvre d’Agnès Varda” in Etudes Cinématographiques: Agnès Varda. Paris: Lettres Modernes, 1991.

Berger, John, and Jean Bohr. Another Way of Telling: A Possible Theory of Photography. Bloomsbury, 1982.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2013.

Brunette, Peter. Michael Haneke. University of Illinois Press, 2010.

Bullock, Michael. “The Spectrum” [Interview with Gage of the Boone and Raúl de Nieves], Apartamento: An Everyday Life Interiors Magazine, no.17, 2016, p.127.

Butin, Hubertus. Gerhard Richter’s Editions and The Discourses of Images. In Gerhard Richter Editions 1965–2013, edited by Hubertus Butin, Stefan Gronert, and Thomas Olbricht. Hanje Cantz, 2014.

Cacioppo, J. T., and L. C. Hawkley. “Perceived Social Isolation and Cognition.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol. 13, no. 10, 2009, pp. 447–454.

Coman, Alina. Tehnici de comunicare: proceduri şi mecanisme psihosociale. C.H. Beck, 2008.

Eichler, Dominic, and Wolfgang Tillmans. “Look, Again.” Frieze, no.118, October 2008, p.233.

Emerson, R. M., Rachel I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. University of Chicago Press, 2011, pp. 21–39.

Exupéry, Antoine de Saint. The Little Prince, translated by Katherine Woods. 1943.

Flores, Nona C. Animals in the Middle Ages: The Book of Essays. 1996.

Gelder, Ken. Subcultures: Cultural Histories and Social Practice. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Godfrey, Mark. Worldview. In Wolfgang Tillmans 2017, edited by Chris Dercon, Helen Sainsbury, and Wolfgang Tillmans, Tate, 2017, pp.14–76.

Guerra, Carles. Notre Histoire, Catalogue of the Exhibition. Paris: Palais de Tokyo, 2006.

Harvey, David. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. United Kingdom: Verso, 2012.

Hatto, Arthur Thomas. The Nibelungenlied. Penguin Books, 1973.

Hegel, Georg W. F. Philosophy of Right. London: Oxford University Press, 1975.

Hertel, Christiane. Vermeer: Reception and Interpretation. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Higgie, Jennifer. Sarah Jones. Le Consortium, 2000.

hooks, bell. “Between Us: Traces of Love—Dickinson, Horn, Hooks.” In Earths Grow Thick, Wexner Center for the Arts, 1997.

Hurley, Neil P. Soul in Suspense: Hitchcock’s Fright and Delight. Scarecrow Press, 1993.

Jenkins, Martin. …and the Situation of the Spectacle. Society of the Spectacle, 2009.

Jones, Sarah. Sarah Jones. Le Consortium, 2000.

Jones, Steven Swann. The Fairy Tale. Routledge, 2013.

Kordecki, Lesley. “Making Animals Mean: Speciest Hermeneutics in the Physiologus of Theobaldus.” In Nona C. Flores, ed., Animals in the Middle Ages: A Book of Essays, Garland Publishing, Inc., 1996, pp. 85–101.

Kris, Ernst. Psychoanalytic Explorations in Art. International Universities Press, Inc., 1988.

Kurland, Justine. Interview by Sasha Wolf, 2017.

LiDonnici, Lynn R. “Compositional Patterns in PGM IV (= P.Bibl.Nat.Suppl. Gr. No. 574).” The Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists, vol. 40, no. 1/4, 2003, pp. 141–178.

Lüthi, Max. The Fairytale as Art Form and Portrait of Man. Indiana University Press, 1987.

Lüthi, Max. Once Upon a Time: On the Nature of Fairy Tales. F. Ungar Pub. Co, 1976.

Mikuriya, Junko Theresa. A History of Light: The Idea of Photography. Bloomsbury, 2017.

Nochlin, Linda. Realism. Penguin Books, 1985.

Richie, Donald, and Ian Buruma. The Japanese Tattoo. 1st ed., Weatherhill, 1989, pp. 60–61.

Rancière, Jacques. Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy. University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

Ricœur, Paul. Time and Narrative, translated by Kathleen McLaughlin and David Pellauer. University of Chicago Press, 1984.

Scott, Jennifer, and Helen Hillyard. Rembrandt’s Light. London: Philip Wilson, 2019.

Slyce, John. On Time, Performative Realism: The Photographs of Sarah Jones. Museum Folkwang, 2000.

Smith, Allison. Agnes Varda. Manchester University Press, 1998.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. Penguin Modern Classics, 2008.

Sullivan, Nikki. Tattooed Bodies: Subjectivity, Textuality, Ethics, and Pleasure. 2001.

Sussman, Elisabeth. Nan Goldin: I’ll be Your Mirror. Whitney Museum of American Art, 1996.

Swann Jones, Steven. The Fairy Tale: The Magic Mirror of the Imagination. 1995.

Troncy, Eric. Sarah Jones. Le Consortium, 2000.

Turner, Victor. On the Edge of the Bush. 1985.

Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process. 1995.

Vasudeven, Alexander. “Reassembling the City: Makeshift Urbanisms and the Politics of Squatting in Berlin.” The Autonomous City: A History of Urban Squatting. Verso, 2017.

Vergne, Jean-Charles, and Clement Cogitore. Le Prix Marcel Duchamp. Silvane Editoriale, 2018.

Wood, John. Design for Micro-Utopias: Making the Unthinkable Possible. 1st ed., Routledge, 2007.

Young, V. Tattooed Selves: Identity(s) in Flesh. Routledge, 2000.