Close Considerations

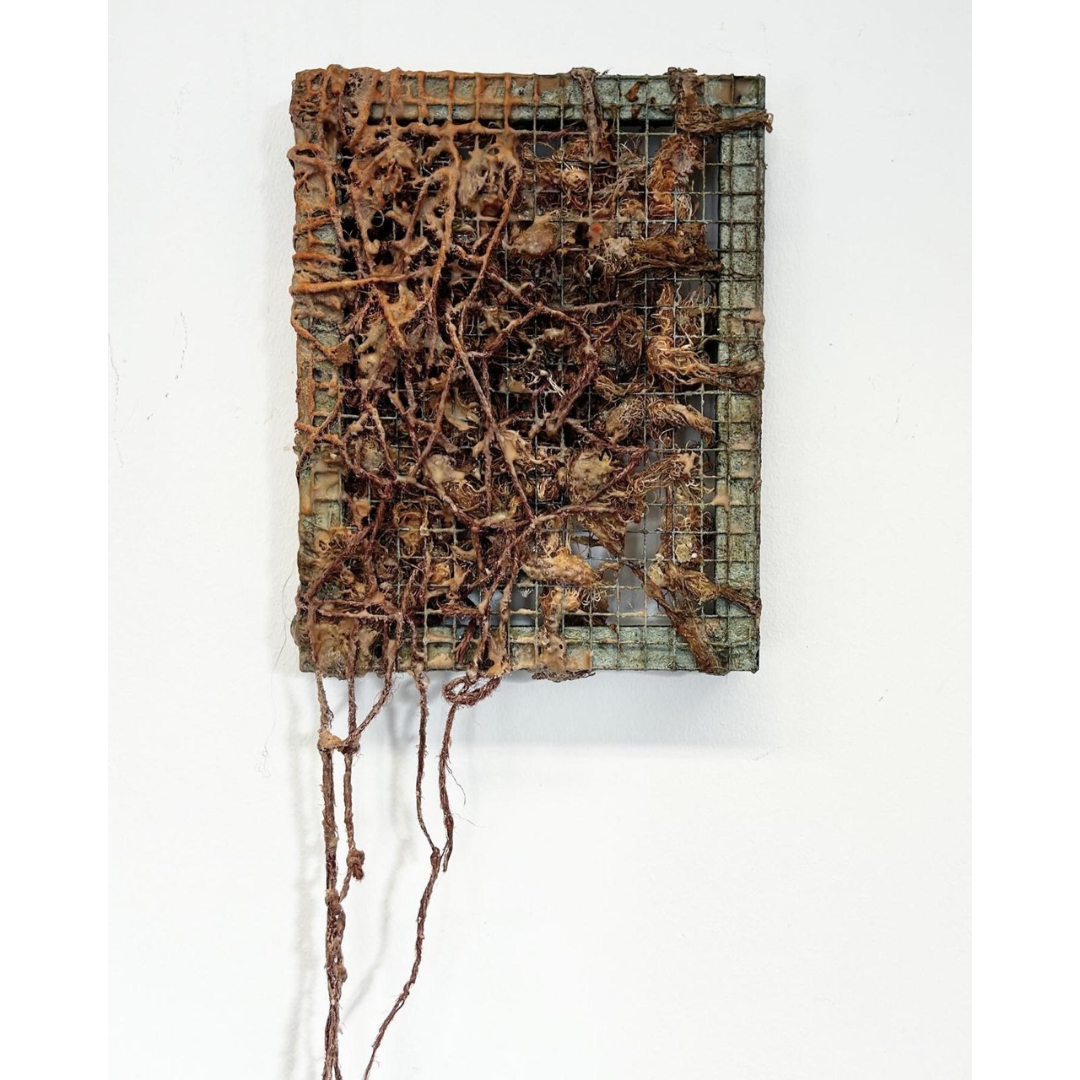

Ecological and Bodily Decay: The Feeling When You Walk Away explores ecological destruction alongside bodily oppression, confronting viewers with textures that evoke both attraction and repulsion. Napoli’s aesthetic, “radically materialistic and corporeal,” demonstrates deliberate ugliness, embracing “the limp, the pliable, the cheap” (Pincus-Witten, 1987, p.47).1 These forms echo Gericault’s painting of the body as “the site of suffering, pain and death” (Nochlin, 2001, p.17),2 foregrounding humanity’s destructive impulses.

Contamination: Materials such as beeswax, iron oxide, and coarse ropes produce a tactile sensation of organic contamination. Wax dripping onto rusted grids forms parasitical networks, appearing simultaneously alive and deteriorating. This texture, “heavily textured…ragged-edged resin” (Lippard, 1992, p.100),3 conveys the work’s inherent ambiguity. Repetition exaggerates the absurd, reinforcing the tension between order and chaos (Nemser, 2002, p.11).4

Inside-Out Bodies: Napoli’s inverts bodily imagery, rendering internal forms outwardly visible, creating grotesque yet clinical surfaces. She furthers the bodily fragmentation seen in Gericault’s art, turning recognisable human forms into nebulous, mutilated visions (Nochlin, 2001, p.22).5 Her biomorphic structures, evocative of decay, blood, and coagulation, blur distinctions between human and ecological forms. These forms exist at the fragile boundary “between life and death” (Schiff, 2015, p.121).6

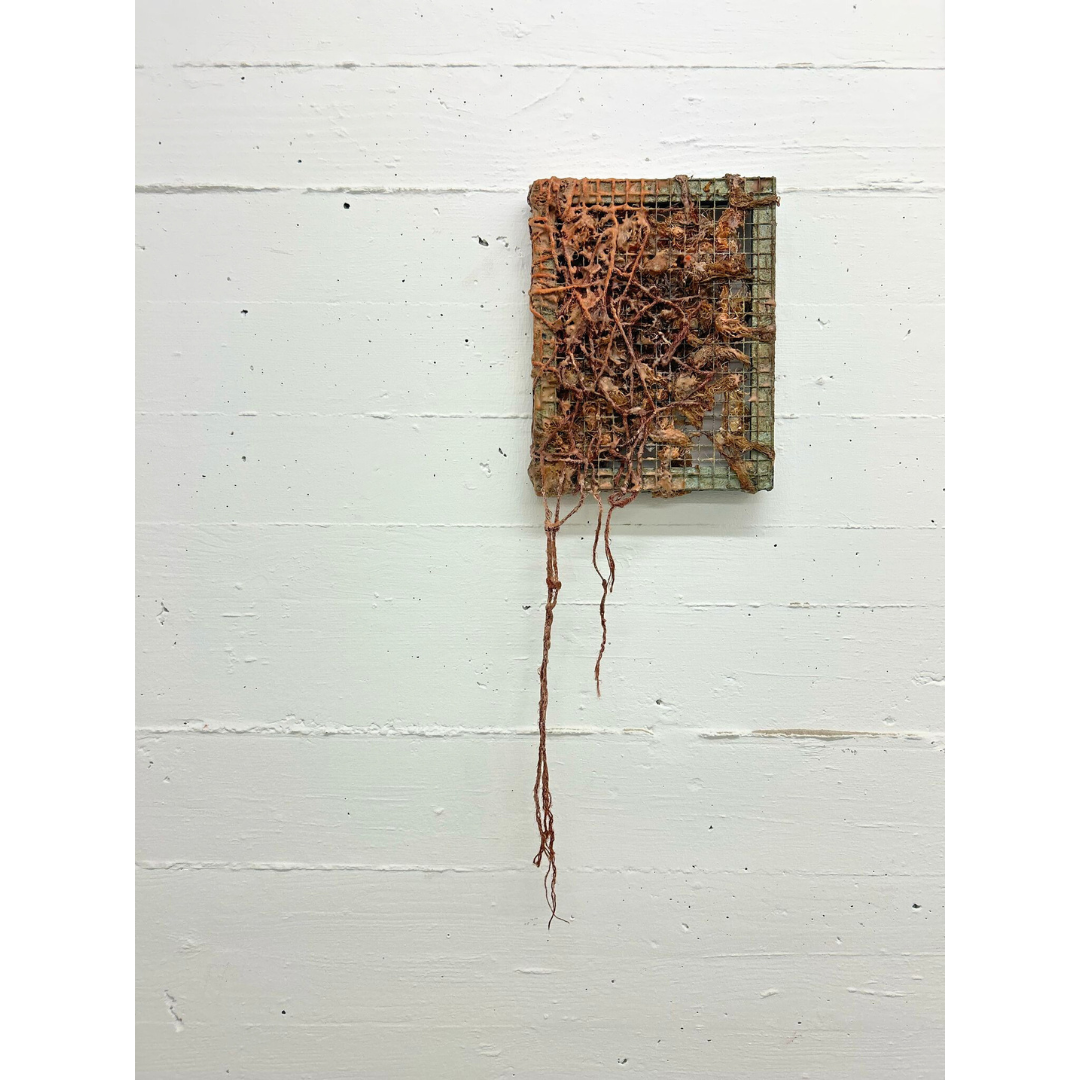

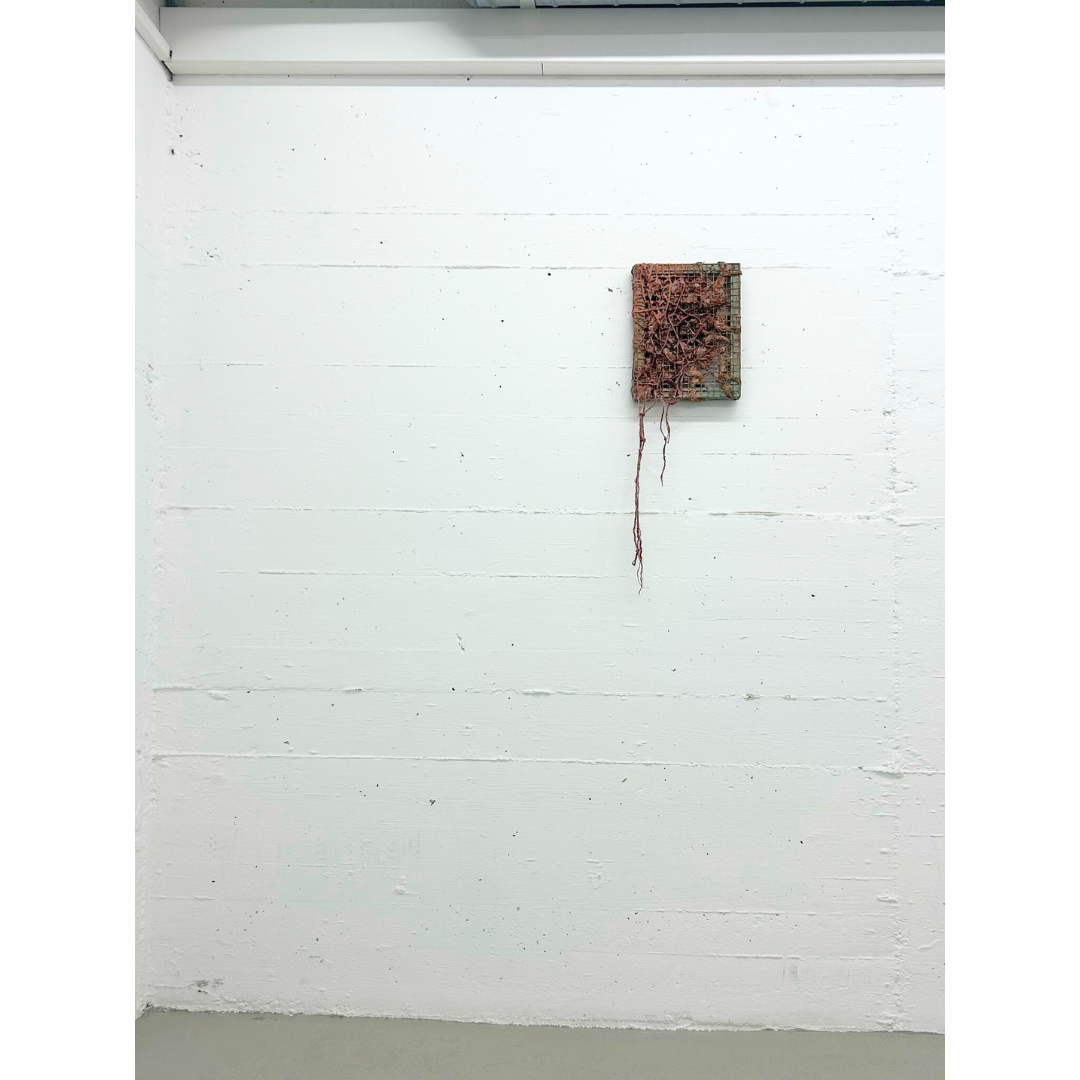

Spatial Invasion: Sized to match the human head and hung at eye-level of an average human, the piece becomes a distorted mirror that invades viewers’ personal space. Ropes extend outward like tentacles or roots, recalling threats of bodily invasion or contamination. This spatial confrontation mirrors Michel Foucault’s panoptic schema, activating psychological unease and self-awareness (Foucault, 1977, p.205).7

Ritual, Cruelty, and Melancholy: Incorporating ropes symbolic of Christ’s blood, Napoli’s sculpture evokes religious drama, cruelty, and melancholic detachment from nature. Echoing Nietzsche, it highlights the human craving for spiritualised cruelty, inherent in both religious ecstasy and tragedy (Nietzsche, 1967, pp.176-7).8 Drawing on Baudelaire’s “spleen,” it conveys a deep sadness, alienation, and introspective self-destruction. This thematic layering reinforces the work’s critique of human cruelty and existential unease.

1 Pincus-Witten, R. (1987). Postminimalism. Thames and Hudson.

2 Nochlin, L. (2001). The Body in Pieces: The Fragment as a Metaphor of Modernity. Thames & Hudson.

3 Lippard, L. (1992). Eva Hesse. New York: Da Capo Press.

4 Nemser, Cindy. "A Conversation with Eva Hesse (1970)." In Eva Hesse 1936-1970, edited by Nixon, Mignon, ed. Eva Hesse. Essays and interview by Cindy Nemser, Rosalind Krauss, Mel Bochner,

5 Nochlin, L. (2001). The Body in Pieces: The Fragment as a Metaphor of Modernity. Thames & Hudson.

6 Schiff, R. (2015). Richard Serra: Forged Steel. David Zwirner.

7 Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan. Penguin Books.

8 Nietzsche, F. (1967). Beyond Good and Evil, trans. Helen Zimmern. George Allen and Unwin Ltd.

Process

Material Experimentation and Reworking: Napoli’s creative process involves extensive experimentation, reworking existing pieces into new forms. She extends the grid structure from Argument in the Age of Desolation (2023) applying resin to create rigid yet organic textures: “dipped in resin and hardened,” (Lippard, 1992, p.141).1 Her practice emerges intuitively, transforming materials through spontaneous dialogue rather than preconceived design.

Serendipity: The artist uses beeswax and epoxy resin, letting wax drip and saturate the base, then solidifying it with resin to stabilise dynamic forms. This interplay of materials invokes the interconnectedness of creation and destruction, visually demonstrating the flux of nature and artifice. Napoli’s hand allows “accident [to become] an unknown form of life” (Focillon, 2007, p.36),2 activating spontaneous material transformations.

Contamination: By accelerating oxidation with copper powder, vinegar, and salt, Napoli creates a green patina evoking ancient contamination. This effect reinforces a sense of “fracture” and “permeation” (Schiff, 2015, pp.124-5),3 embedding decay into the work’s fabric. Such deliberate deterioration mirrors Foucault’s “discipline” that “extracts from bodies maximum time and force” (1977, p.220),4 visually manifesting control and entropy.

Erotic and Existential Themes: Napoli explores themes of sexual tension through biomorphic forms and phallic imagery, expressing “schizziness of autoeroticism coupled with fanatical order” (Krauss, 2002, pp.51-52).5 Sculptural shapes challenge the viewer physically and conceptually, evoking simultaneous “desire and destruction” (Fer, 2002, p.81).6 Surfaces embody existential longing, reflecting Sartre’s notion of perpetual, unfulfilled desire (Sartre, 2003, p.128).7

Archaeological Vision: Suggesting archaeological discovery from a distant future, Napoli’s work acts as an abstracted, impersonal self-portrait capturing collective anxieties. The open-ended arrangements reflect societal cycles of “creation and destruction,” existing beyond fixed interpretations (Lippard, 1992, p.164).8 Her elaborate, Dadaist-inspired titles amplify the absurdity, ironically highlighting human attempts at making conclusive sense (Mussman, 1966;9 Pincus-Witten, 1987, p.51).10

1 Lippard, L. (1992). Eva Hesse. New York: Da Capo Press.

2 Focillon, H. (2007). In Praise of Hands: Manual Skill and Its Practice. Zone Books.

3 Schiff, R. (2015). Richard Serra: Forged Steel. David Zwirner.

4 Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan. Penguin Books.

5 Krauss, R. (2002). Eva Hesse, October Files. MIT Press.

6 Fer, B. Anne M. Nixon, and Mignon Nixon. (2002) OCTOBER files 3. The MIT Press.

7 Sartre, J.-P. (2003). Being and Nothingness, trans. Hazel E. Barnes. Routledge.

8 Lippard, L. (1992). Eva Hesse. New York: Da Capo Press.

9 Mussman, T. (1966). "Duchamp and the Language of Puns", Artforum.

10 Pincus-Witten, R. (1987). Postminimalism. Thames and Hudson.

References

Eva Hesse: Napoli diverges from Eva Hesse by beginning at a stage where opposites have already been juxtaposed, moving beyond mere formal contradictions toward unification. Her repetition exaggerates meaning to “an absurd level,” expanding upon Hesse’s dialectics of humour, death, and emotive ephemerality (Lippard, 1992, p.201).1 Unlike Minimalism’s rigid industrial materials, Napoli employs raw, found objects, enhancing organic complexity and process-driven expressivity (Pincus-Witten, 1987, p.11).2

Anselm Kiefer’s Allegorical Dimensions: She occupies a space between Anselm Kiefer’s turbulent textures and Eva Hesse’s organic forms, creating layered works that produce “allegorical reading” (Fisher, 1985, p.106).3 Her autotelic practice “self-forming and self-identifying” (Schiff, 2015, p.121)4 relies on intuitive engagement with materials. And like Donald Judd, she embraces “actual space” as intrinsically more potent than two-dimensional surfaces, with each piece asserting itself clearly within a unified whole (Judd, 2016, pp.141-143).5

Surrealism and Absurdist Humour: Inspired by the detached absurdity of the French cartoon Time Masters, Napoli integrates humour and existential detachment into her sculpture practice. Her work, while structured in relation to other pieces, retains independence and spontaneity, breaking from fixed narrative order (Schiff, 2015, p.113).

Post-humanism: Exploring Post-humanism and Post-Internet culture, Napoli represents humans metaphorically as self-destructive viruses within ecological and social systems. Her sculptures reflect Nietzsche’s assertion that “insanity in groups…is the rule” (Nietzsche, 1967, p.98).6 Through simulations and fragmented forms, Napoli questions humanity’s programmed role within broader, uncontrollable systems. Her biomorphic structures blur boundaries between human, animal, and technological continuums in existential uncertainty.

1 Lippard, L. (1992). Eva Hesse. New York: Da Capo Press.

2 Pincus-Witten, R. (1987). Postminimalism. Thames and Hudson.

3 Fisher, J. (1985). "Saprophytic Allegories", in October, pp.106–11.

4 Schiff, R. (2015). Richard Serra: Forged Steel. David Zwirner.

5 Judd, D. (2016). Complete Writings 1959–1975. Judd Foundation.

6 Nietzsche, F. (1967). Beyond Good and Evil, trans. Helen Zimmern. George Allen and Unwin Ltd.