Close Considerations

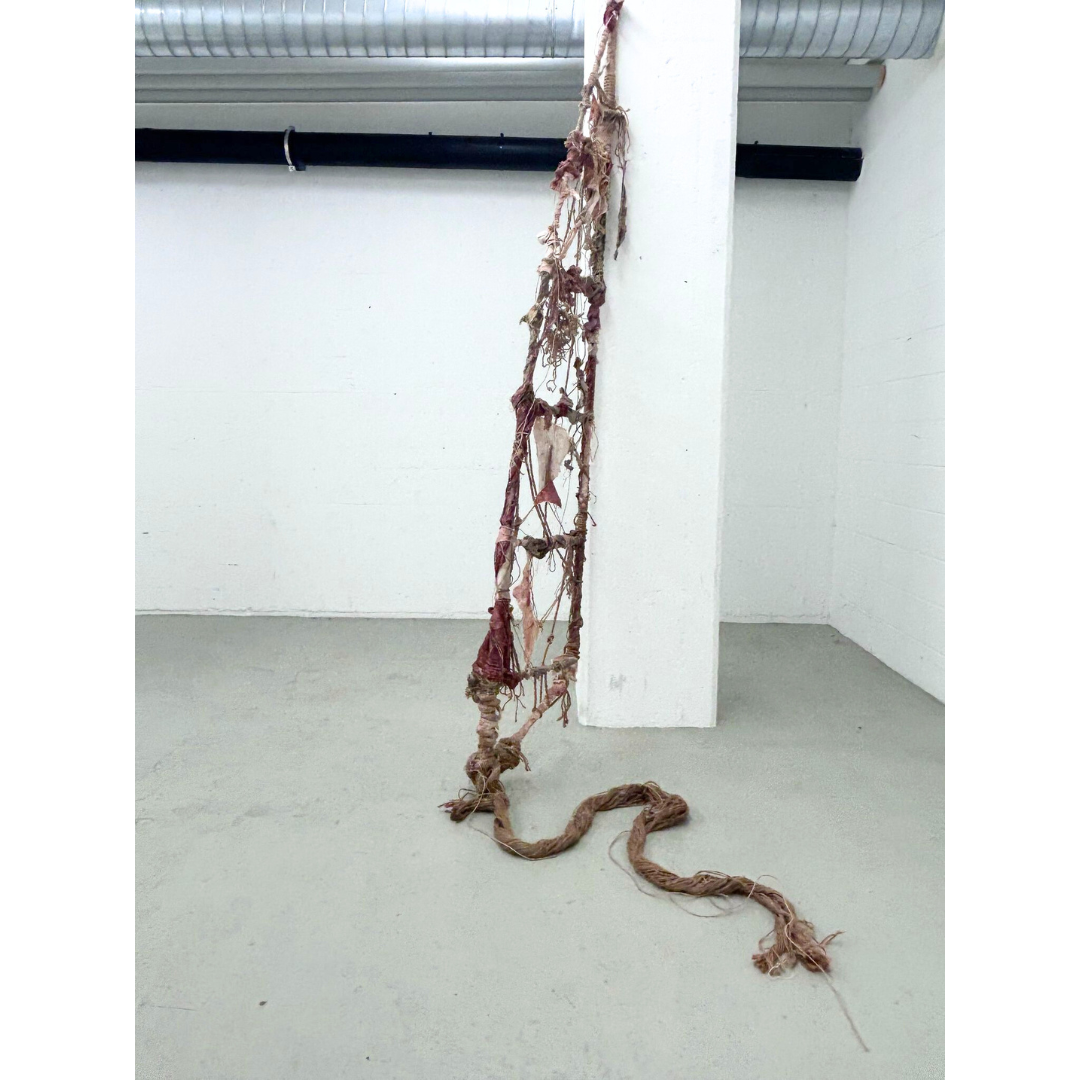

Symbolic Elements and Societal Grids: Napoli’s sculpture began with a found shelf and sail carcass, symbolising confinement, time, and societal constraints. The abstracted sail reflects potential progress and failure, structured by grids representing imposed societal order. Napoli employs repetition to reveal how grids impose "solid separations," defining "compact hierarchical networks" (Foucault, 1977, p.220).1

Materials and Texture: The use of rusted metal and organic fabrics alludes to decay, loss, and the passage of time, embodying human vulnerability. Beeswax and iron oxide "signify the tension between the macro and microcosm" (Schiff, 2015, p.124),2 while rough surfaces recall "the limp, the pliable, the cheap" (Pincus-Witten, 1987, p.47).3 Fabrics are "roughly sewn," preserving life's marks and signifying human touch (Lippard, 1992, p.122).4

Theatricality: The sculpture appears to hover "on the brink of function and association," (ibid., p.151). The spatial relationship is theatrical, implicating viewers “not just physically but psychically" (Fried, 1998, p.154).5 Napoli’s work occupies thresholds between exposure, concealment, stability, and collapse.

Scale, Intimacy, and Viewer Interaction: Sized to mirror the human form, the sculpture creates an intimate, bodily dialogue with the viewer. Scale amplifies the emotional impact, echoing postminimalist principles of "complex purposes" made clear by form (Judd, 2016, p.143).6 Placement within darkened spaces of the gallery suggests neglect, enabling personal discovery and the resulting emotional impact, which may differ if the work was front and centre. Such installation strategies "sensitise viewers to the qualities" of the artwork and its surroundings (Schiff, 2015, p.113).

Ecological Renewal: Napoli’s forms appear as if consumed by mycelium, natural decomposition, and renewal within life’s cyclical processes; cells in a parasitical body, driven by instinctual patterns. The work confronts existential themes of creation and destruction, revealing human consciousness as perpetually "haunted by a totality" beyond its grasp (Sartre, 2003, p.114).7

1 Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan. Penguin Books.

2 Schiff, R. (2015). Richard Serra: Forged Steel. David Zwirner.

3 Pincus-Witten, R. (1987). Postminimalism. Thames and Hudson.

4 Lippard, L. (1992). Eva Hesse. New York: Da Capo Press.

5 Fried, M. (1998). Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews. University of Chicago Press.

6 Judd, D. (2016). Complete Writings 1959–1975. Judd Foundation.

Process

Accidental Discovery and Intuition: Napoli’s sculpture emerged from serendipitously discovering a found object, allowing materials themselves to dictate the final form. Her intuitive approach recalls Donald Judd’s belief that in "three dimensions…almost anything" credible can arise (Judd, 2016, p.141).1 Her method embraces chance, harnessing "the unpredictable element beyond the realm of spirit…accident" (Focillon, 2007, p.34),2 balancing “manipulation and submission” dynamically (Schiff, 2015, p.124).3

Material Exploration: Experimenting with techniques such as rusting metal with vinegar and steel wool, the artist engages physically and emotionally with her materials. She wraps elements with fabric and adds other layers, care juxtaposed with violence (Fowle, Sirmans, & Morgan, 2016, p.40).4 This tactile approach transforms ordinary materials, creating "a push and pull between care and violence, healing and hurting, growing and aging" (Schiff, 2015, p.124).

Iterative Process: Napoli’s sculptural process is iterative, involving continual experimentation and reflection, where "work comes out of work.” Her method is like a dance, shifting from chaos into paradox (Lippard, 1992, p.185).5 Each stage reveals "frailty and strength, chaos and order…absence and presence" (Nixon, 2002, p.175),6 engendering emotional engagement through repeated revisions.

Precarity: Napoli deliberately constructs precarious forms that embody instability, mirroring human existential vulnerability and incompleteness (Sartre, 2003, p.113).7 Her sculptures reflect "tension between looseness and tightness," suggesting both liberation and constraint (Lippard, 1992, p.187). Fragile structures become metaphors for the precariousness of human life, capturing "the full weight of the human being…in all its impulsive vivacity" (Focillon, 2007, p.34).

Repetition, Absurdity, and Authenticity: Repetition exaggerates meaning in Napoli’s work, amplifying the absurdity as a deliberate aesthetic and conceptual choice. As Eva Hesse noted, "if something is absurd, it’s much more greatly exaggerated…if it’s repeated" (Nemser, 2002, p.11).8 This process describes the paradoxical pursuit of authenticity, where "the true authentic self as sincerity…motivates us but also evades us" (Sartre, 2003, p.86), transcending mere representation (Schiff, 2015, p.121).

1 Judd, D. (2016). Complete Writings 1959–1975. Judd Foundation.

2 Focillon, H. (2007). In Praise of Hands: Manual Skill and Its Practice. Zone Books.

3 Schiff, R. (2015). Richard Serra: Forged Steel. David Zwirner.

4 Fowle, K., Sirmans, F., & Morgan, J. (2016). STERLING RUBY. Phaidon.

5 Lippard, L. (1992). Eva Hesse. New York: Da Capo Press.

6 Nixon, M. (ed.). (2002). Eva Hesse. Essays and interview by C. Nemser, R. Krauss, M. Bochner, B. Fer, A. M. Wagner, and M. Nixon. OCTOBER files 3. The MIT Press.

7 Sartre, J.-P. (2003). Being and Nothingness, trans. Hazel E. Barnes. Routledge.

8 Focillon, H. (2007). In Praise of Hands: Manual Skill and Its Practice. Zone Books.

9 Nemser, Cindy. "A Conversation with Eva Hesse (1970)." In Eva Hesse 1936-1970, edited by Nixon, M.

References

Surrealism: Napoli’s practice is deeply influenced by surrealist aesthetics, characterised by dream-like qualities and subconscious exploration. Her forms create tension between animate and inanimate states (Lippard, 1992, p.33).1 These sculptures "infer, but they do not depict" (Pincus-Witten, 1987, p.49),2 embodying "primitive or dreamlike incarnation, wholly disguised as abstraction" (Lippard, 1992, p.185).

The Legacy of Richard Serra: The artist engages with Richard Serra’s conception of instability, form, and emotional impact, reflecting a dynamic between structure, space and the viewer’s body. Her autotelic practice is "self-forming and self-identifying," compelling direct physical and existential experiences (Schiff, 2015, p.121).3 As Serra states, unforeseen elements hold "the possibility of transforming how you see," influencing thought itself (ibid., p.110).

Eva Hesse and Louise Bourgeois: Her use of fabric draws significantly from Eva Hesse, emphasising ephemerality, and time through "rags…street detritus" (Pincus-Witten, 1987, p.47). These materials form "intricately controlled labyrinth[s]" with paradoxically "strong and vulnerable" moods (Lippard, 1992, p.100). Louise Bourgeois similarly inspires Napoli’s material explorations, revealing emotional depths and aesthetic possibilities in tactile, layered textiles (Mussman, 1966;4 Genosko, 2002, p.97).5

Mythological Allegory: The artist’s sculptures reference existential narratives like Ulysses’ Odyssey, humanity’s struggle for meaning amid adversity and decay. Her sculptural forms evoke Théodore Géricault’s bodies, transformed from subjects into "lifeless, gruesome fragments," suggestive of survival and dramatic decay (Nochlin, 2001, p.22).6 Nietzschean self-cruelty and Sartre’s existential "lack" further frame her inquiry into human suffering and consciousness (Nietzsche, 1967, pp.177-8;7 Sartre, 2003, p.113).8

Sterling Ruby: Her work’s decay references Sterling Ruby’s "alien" forms, confronting viewers with complex realities hidden behind loud surfaces (Sirmans, 2016, p.40).9 These layered, absurdist compositions complicate traditional convictions, emphasising creativity as "transversality" against inherited structures (Genosko, 2002, p.71).

1 Lippard, L. (1992). Eva Hesse. New York: Da Capo Press.

2 Pincus-Witten, R. (1987). Postminimalism. Thames and Hudson.

3 Schiff, R. (2015). Richard Serra: Forged Steel. David Zwirner.

4 Mussman, T. (1966). "Duchamp and the Language of Puns", Artforum.

5 Genosko, G. (2002). Félix Guattari: An Aberrant Introduction. Continuum.

6 Nochlin, L. (2001). The Body in Pieces: The Fragment as a Metaphor of Modernity. Thames & Hudson.

7 Nietzsche, F. (1967). Beyond Good and Evil, trans. Helen Zimmern. George Allen and Unwin Ltd.

8 Sartre, J.-P. (2003). Being and Nothingness, trans. Hazel E. Barnes. Routledge.

9 Fowle, K., Sirmans, F., & Morgan, J. (2016). STERLING RUBY. Phaidon.