Ophélie Napoli

My Guts on Your Table

Installation shot from Ophélie Napoli's solo exhibition My Guts on Your Table, 2023, in Zurich, Switzerland.

Sunend is proud to present works by Ophelie Napoli from her landmark solo exhibition My Guts on Your Table, held in Zurich in 2023, which reveals a deeply autotelic practice in which decay, absurdity, violence, and tenderness emerge as indivisible, coextensive forces. Napoli’s oeuvre is an uncompromising confrontation with the mechanisms that shape our human condition. Her use of beeswax, rusted canvas, and iron, for instance, are active material agents within a system of renewal, integral to the sculptural articulation of entropic processes and cyclical transformation. Her work lies in the potent interstice between Eva Hesse’s visceral organicism and Anselm Kiefer’s textured mythicism, where collapse and transformation operate at once.

Members at the Members' Preview for Eva Hesse: A Memorial Exhibition, March 5, 1973. Image courtesy of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery Digital Assets Collection and Archives, Buffalo, New York.

Ontology, Material Agency, and Aesthetic Systems

In a world seemingly dismembered by ecological crises, Napoli's work forms new anatomies of meaning, transmuting the grandiose with the grotesque, the sacred with the scatological. Her practice enables us to glean aspects of movements past like Minimalism and Post-Minimalism otherwise undiscerned (Ingrid Sischy, 1981, p.67), made visceral again through her radical sincerity. Her work expresses both "cultural history and art history as open-ended, unstable and continuously renewed," operating simultaneously in rupture and continuity.1

Ophélie Napoli in her studio testing the elasticity and configuration for a sculpture.

In the works presented here, one sees an "utter wilfulness" and operatic ambition (Liebmann, 1982, p.90), as a tangible credence that radiates from her own being into her works.2 The emotional intensity of the pieces is never separated from the materiality. They are, in fact, one and the same. The tension in Napoli’s work, between softness and steel, vertical and horizontal, can be argued as the space of life. In the allegorical underpinnings of her pieces "a torsion takes place that gives the work a texture of duplicity" (Fisher, 1985, pp.106-11).3 Her works, like Kiefer's, are saprophytic associations in which narrative leads to decomposition, revealing to us new thresholds of meaning.

Kiefer and Napoli share an affinity for the grand gesture, but while the former’s use of cultural and historical references often tilts toward the monumental, the latter’s mythologies are embodied and immediate. Both employ organic materials like straw, ash, lead in Kiefer’s case, rust and beeswax in Napoli’s. But while his imagery gestures toward the tragic sublime, her tragicomic use of materials seems to oscillate between structural breakdown and comedy, a different kind of sublime. The grotesque scale and humour of her titles destabilise any tendency toward monumentalism, pulling it back into the body and its abject messiness.

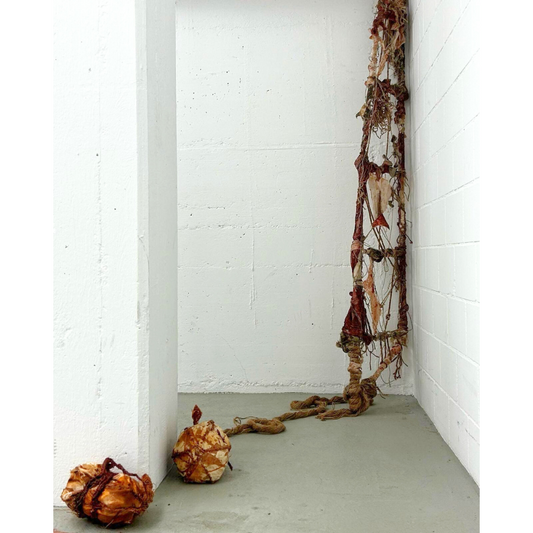

Installation shot from Ophélie Napoli's solo exhibition My Guts on Your Table, 2023, in Zurich, Switzerland.

Her divergence from Eva Hesse is equally generative. Hesse’s emphasis on contradiction, soft vs hard, and loose vs tight, for instance, is the point of departure for Napoli. While Hesse’s work edged towards decay, where her works deteriorated over time which she did not live long enough to see, since she passed tragically in her mid-thirties, Napoli’s practice, on the other hand begins at the decaying. In a way, her practice marks the evolution on Hesse’s. This can be seen in her dismantling of oppositional binaries into a tense simultaneity. Her use of rigid tubing alongside pliable textiles and melted beeswax offers a form in which contradiction is a structural necessity.

The artist’s process is craft-based and entails stitching, lacing, and welding iron to manipulate rigid structures, integrating the sculptural impulses of the postminimalist Richard Serra. Serra’s emphasis on "weight" and "measure" (Schiff, 2015, pp.124-5)4 can be found expanded in Napoli’s practice to include Fracture, Permeation, and Flux. While Serra’s pieces confront the body through scale and density, Napoli’s envelop, leak, and sag, transforming the viewer’s encounter into something tactile, ambiguous, and visceral. This distinction reflects Napoli’s concern with subjectivity, vulnerability, and the limits of agency within spatial and social constructs.

Tilted Arc, Richard Serra, 1981 in New York

Entropy and Embodiment

Napoli’s handling of repetition and gesture is described by her capacity to create tension between internal coherence and expressive fragmentation. Hesse’s signature use of repetition in works like Repetition Nineteen III (1968) acts as a structure through which absurdity and variation manifest. Napoli mirrors this strategy, as a starting point from which to proceed organically. Her iterations can be understood as slow-motion convulsions. In pieces such as This Ship Has Sailed (all works 2023), each unit’s repetition seems to reify failure, foregrounding collapse as form.

This Ship Has Sailed, 2023

Found rusty steel ladder beeswax, sewn fabric, string and rope

£3000

Central to the artist's vision is the disintegration of form as a pathway to new being. Raised in dense urban environments such as Hong Kong, where she witnessed skyscrapers rise and fall and rise again with tiny humans swarming around, she views humanity as part of a parasitic ecosystem, where expansion and rot are co-constituent. In this way, her conceptual framework is congruent with Edward O. Wilson's characterisation of insect colonies as diffuse organisms, where the boundaries between the individual and the collective merge into a single metabolic force (Wilson, 1975, p.399).5

The materiality through beeswax, iron oxide, and rust is deeply corporeal. Iron, found in both meteorites and blood, describes the shared atomic heritage of life. Time is also embedded in her works, as the process relies on discolouring, and decay in the "push and pull," of seaming, joining, breaking, and wrapping. As Henri Focillon reminds us, the artist’s hand "grasps, it creates, at times it would seem even to think" (Focillon, 2007, p.25).6

Ophélie Napoli processing raw materials.

Grid, Rupture, and Transversality

Napoli’s grid, present in works likeArgument in the Age of Desolation and The Feeling When You Walk Away, holds the tension between control and flux. As Rosalind Krauss observed, "The grid declares the space of art to be at once autonomous and autotelic" (Krauss, 1978, pp.3-4).7 But Napoli destabilises this autonomy by extending her ropes beyond the frame, insinuating a continuity that undermines containment. The ropes in this sense evoke anatomical veins leaking from a body too expansive for its skin.

My Guts on Your Table, 2023

Found wooden table, beeswax, sewn fabric, string and rope

£4000

Although steeped in theoretical study of scientific organisms, philosophy and art history, her process is intuitive and self-directed, emerging naturally from the contingencies of engagement with the raw materials. This is most clearly seen in My Guts on Your Table, where a suspended skeletal form, stitched and rusted, leads the viewer's gaze into an empty wall, a choreography of failed direction. The work is impactful with its potent humour and brutality, and delicacy and crudeness as the table suggests domestic communion, but the guts spilled across it point to violence, vulnerability, and irretrievable exposure.

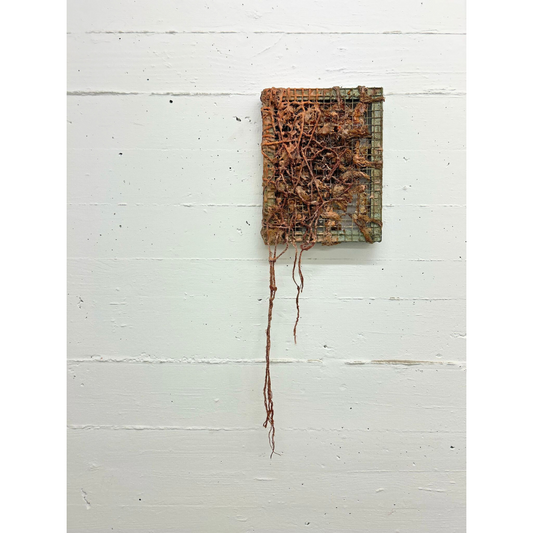

Argument in the Age of Desolation, 2023

Beeswax, metal grid, rusted canvas, string and rope

£4000

In Argument in the Age of Desolation, Napoli uses a found metallic grid warped and reconfigured with rusted canvas and knotted threads. The grid here allegorises structure of socio-political constraint. Like Michel Foucault’s disciplinary apparatus (1977),8 the work operates as a site of entrapment and revolt. The grid as prison, as panopticon, is transgressed by the organic seepage of its contents, a literal and metaphoric bleeding beyond bounds. The work’s posture tilted, sagging, incomplete reinforces its resistance to closure and authority.

In The Feeling When You Walk Away, the grid form is lightened, rendered more fragile, its edges receding into hanging fibres. Here the structure is barely able to hold itself, evoking Guattari’s transversality (Genosko, 2002, p.97): a form that bridges, fractures, and reterritorialises across fixed systems.9 The threads extend into space like nerve endings, creating a spatial drawing that catches the viewer mid-step, reorienting their relation to the work and to the architecture itself.

The Feeling When You Walk Away, 2023

Beeswax, metal grid, rusted canvas, string and rope

£1500

Theatricality, Instability, and Spatial Affect

The influence of theatricality is felt throughout Napoli’s oeuvre. Her spatial configurations demonstrate a kinetic relationality, wherein smaller sculptural units are systematically calibrated in proximity to larger, architectonic forms. This intentional heterogeneity induces a dynamic perceptual instability, rendering the installation a fluid topography of differential material densities rather than a static assemblage of discrete objects. The viewer is implicated as a co-participant in the aesthetic field, encountering each work as a node.

As Michael Fried describes in his critique of literalism, the temporal unfolding of such works introduces a “theatrical” presence (Fried, 1998, p.167).10 The pieces are surrogate bodies, possessing a hollowness that evokes inner life and psychic depth (ibid., p.156). The sculptures appear to lean, and to reach. They draw the viewer into a choreography without an ideal vantage point as such, or totalising perspective, but fragments, partial views, and sudden confrontations.

The Feeling When You Walk Away, 2023

Beeswax, metal grid, rusted canvas, string and rope

£200 - 500

Phenomenological Immersion, and Displacement

The phenomenological encounter with Napoli’s work produces sensations of imbalance or unease. This is especially true in installations where scale is manipulated to either dwarf or level with the human body. For example, in My Guts on Your Table, the work’s horizontal sprawl and corporeal forms cause the viewer to hover between forensic observer and intimate participant. Its proximity to the ground and the varied heights of its legs, which make it look like it’s slow-walking, destabilises visual hierarchies and activates what Linda Nochlin identifies as the “abject horizontal” (Nochlin, 2001, p.21), rendering the body simultaneously vulnerable and assertive.11 The experience is one of confrontation between one’s own physicality and the displaced interiority of the work.

Anselm Kiefer, Eisen-Steig, 1986

This affect recalls Jean-Paul Sartre's existential ontology, particularly his notion of Bad Faith: the evasion of authentic being through roles and façades. Napoli’s grotesque, inside-out sculptures reject play with these façades. They are failures by design, glorious failures haunted by the totality they can never be (Sartre, 2003, pp.113-4).12 The artist’s desire, like Sartre’s for-itself, is always haunted by a being it cannot attain. Her practice in a way is about enduring a lack of identity, its yearning, or its displacement.

Absurdity, Cruelty, and Resistance

Rêverie, 2023

Found wood, beeswax, rusted canvas, string and rope

Sold

The humour in her titles, reminiscent of the Dadaists, underscores this existential contradiction. They are elaborate and self-effacing. As Toby Mussman observed of Duchamp, "puns... cast ironic doubt on the ability of any written sentence to make ultimate and absolutely conclusive sense" (Mussman, 1966).13 Napoli embraces this absurdity, creating meaning that mocks its own ambition.

She does not retreat into irony, however. Her work is sincere in its embrace of the contradictions, embodying both Nietzsche’s "will to power" and his disdain for the equalised herd (Nietzsche, 1967, p.84).14 If anything it is more romantic than it is ironic, like the myth of Icarus. Napoli’s art practice is a solitary greatness, a mastery of form that remains open to chance. Her materials are feel raw configured in precarious-seeming structures, which cause a spine-tingling rush through their tension. Yet within this instability is a structurally embedded regulatory precision, a "quarrying" of thought through the hand (Focillon, 2007, p.25). As Linda Nochlin noted of Gericault, the fragmented body becomes a site of suffering and abjection. Napoli expands this, turning the body inside out until what was once abject becomes sovereign. Her vertical arrangements restore the "dignity" denied to horizontal forms (Nochlin, 2001, p.21). As a result, the grotesque becomes the subject, and the object.

In this exhibition, named after the work My Guts on Your Table, these themes coalesce into a total work of art. The whole installed exhibition operates formally as well as psychically. As Fried argued, pejoratively perhaps but still convincingly, such work functions as "a surrogate person," asserting its presence not only in physical space but also in existential terms (Fried, 1998, p.156).15

Untitled (Heart), 2023

Fish net, bamboo sticks, beeswax, rusted canvas, string

varying dimensions

Ophelie Napoli’s practice does not shy from the cruelty of existence. Like Nietzsche’s tragedy, it finds sublimity through the tragedy (Nietzsche, 1967, p.176). Her installations are theatres of failure and excess, of repetition that renders the absurd even more absurd (Nemser, 2002, p.11).16 The grid is transversed by the very materials that sustain it (Genosko, 2002, p.97). Her work reminds us that to make work today is to mine the chaos, to construct coherence from catastrophe, while others may seek to escape it. Her work is a practice of wrestling, of surrendering and shaping simultaneously. In her sculpture and installation works, we see a world revealed, where even the grid bleeds.

Notes

1 Sischy, I. (1981). Artforum (Summer), p.67.

2 Liebmann, L. (1982). "Anselm Kiefer: The Periphery of Knowledge," Art in America, p.90.

3 Fisher, J. (1985). "Saprophytic Allegories", in October, pp.106–11.

4 Schiff, R. (2015). Richard Serra: Forged Steel. David Zwirner.

5 Wilson, E. O. (1975). Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. Harvard University Press.

6 Focillon, H. (2007). In Praise of Hands: Manual Skill and Its Practice. Zone Books.

7 Krauss, R. (1978). "Grids" in October, pp.3–23.

8 Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan. Penguin Books.

9 Genosko, G. (2002). Félix Guattari: An Aberrant Introduction. Continuum.

10 Fried, M. (1998). Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews. University of Chicago Press.

11 Nochlin, L. (2001). The Body in Pieces: The Fragment as a Metaphor of Modernity. Thames & Hudson.

12 Sartre, J.-P. (2003). Being and Nothingness, trans. Hazel E. Barnes. Routledge.

13 Mussman, T. (1966). "Duchamp and the Language of Puns", Artforum. 14 Nietzsche, 1967, p.84

14 Nemser, Cindy. "A Conversation with Eva Hesse (1970)." In Eva Hesse 1936-1970, edited by Mignon Nixon. The MIT Press, 2002.

Selected bibliography

Adorno, T. & Horkheimer, M. (1989). Dialectic of Enlightenment, trans. John Cumming. New York: Verso.

Elderfield, J. (1972). Essays on Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press.

Fisher, J. (1985). "Saprophytic Allegories", in October, pp.106–11.

Focillon, H. (2007). In Praise of Hands: Manual Skill and Its Practice. Zone Books.

Foster, H. (1996). The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century. MIT Press.

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan. Penguin Books.

Fried, M. (1998). Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews. University of Chicago Press.

Genosko, G. (2002). Félix Guattari: An Aberrant Introduction. Continuum.

Judd, D. (2016). Complete Writings 1959–1975. Judd Foundation.

Krauss, R. (1978). "Grids" in October, pp.3–23.

Krauss, R. (2002). Eva Hesse, October Files. MIT Press.

Liebmann, L. (1982). "Anselm Kiefer: The Periphery of Knowledge," Art in America, p.90.

Lippard, L. (1992). Eva Hesse. New York: Da Capo Press.

Mussman, T. (1966). "Duchamp and the Language of Puns", Artforum.

Nemser, Cindy. "A Conversation with Eva Hesse (1970)." In Eva Hesse 1936-1970, edited by Mignon Nixon. The MIT Press, 2002.

Nochlin, L. (2001). The Body in Pieces: The Fragment as a Metaphor of Modernity. Thames & Hudson.

Nietzsche, F. (1967). Beyond Good and Evil, trans. Helen Zimmern. George Allen and Unwin Ltd.

Pincus-Witten, R. (1987). Postminimalism. Thames and Hudson.

Sartre, J.-P. (2003). Being and Nothingness, trans. Hazel E. Barnes. Routledge.

Sischy, I. (1981). Artforum (Summer), p.67.

Schiff, R. (2015). Richard Serra: Forged Steel. David Zwirner.

Simmel, G. (1990). The Philosophy of Money, ed. D. Frisby, trans. T. Bottomore, D. Frisby. Routledge.

Wilson, E. O. (1975). Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. Harvard University Press.